New York City Game

Concrete jungle, Big Apple, City That Never Sleeps, City so nice they named it twice, City of Dreams, Center of the Universe… America’s golf capital? Why not.

It was November 9th of 1895 and Lucy Barnes Brown’s holidays were off to an early start. After a lively morning nine, Mrs. Charles S. Brown (as the papers called her) enjoyed a nice lunch with the other 12 ladies competing at Meadow Brook Club on Long Island, returned to the course and handily won the first-ever U.S. Women’s Amateur. Representing Shinnecock Hills GC (founded in 1891 and open to women from the start), she set the women’s record on a course widely acknowledged at the time to be the most difficult in the country, but she didn’t receive a trophy, or at least not an official one. The USGA had only just been created the year before, and in hastily assembling the tournament there hadn’t been time to sort a prepared award. She was given a silver pitcher instead, but she likely wouldn’t have minded; Lucy was a New Yorker, after all.

The City That Never Sleeps. The Empire City. Gotham. The Center of the Universe… New York City has a long list of monikers, but few would call it the Home of Golf in America—though perhaps they should. In some significant ways, The Big Apple has more claim to the game than any other U.S. city; you might even say American golf started here. True, the game had been in the States for 20 years by the time New York City got its first course, but when it did it wasn’t just New York’s first course, it was everybody’s first course: Van Cortlandt, the first public course in the United States, opened in 1895. In the years surrounding its debut, NYC was the center of the golf universe: the birthplace of the USGA, the PGA of America, and numerous regional clubs, tournaments, pros and top amateurs, including Lucy Barnes Brown. Today its love affair with the game continues, even if city golfers have had to adapt to an obvious lack of green space (or of space in general) with modern driving ranges and practice facilities, top-of-the-line training opportunities and a host of city options that keep the game very much alive year-round. Come here and bring your clubs, just don’t dawdle too much when you’re playing or you’re likely to hear golf balls whistling past your head—and you wouldn’t be the first.

Early Days

“You don’t need to know how to play golf; you don’t even need to play it to get a lot of fun out of the ancient and honorable game. Just go up to Van Cortlandt Park, where the public links are open almost the year round.” So reported a 1910 New York Times piece entitled “Humors of Golf as Played at Van Cortlandt Park,” which turned a rather unkind eye on the golfers at what was then one of three public courses in the city (Forest Park in Queens and the Bronx’s Pelham Bay were the other two). Golf had been all the rage for years when the Times piece was published, and it had some sort of presence as early as 1796, evidenced in an ad that year in the Royal Gazette of New York City for golf clubs and balls. But it really exploded in the late 19th century with the emergence of proper clubs like the Quogue Field Club, located in the Hamptons on Long Island, and the Saint Andrew’s Golf Club in Yonkers, just north of the city, both of which are still in operation. In the city proper, visitors even enjoyed mini-golf on tony hotel rooftops, like that of the Hotel Victoria in Manhattan.

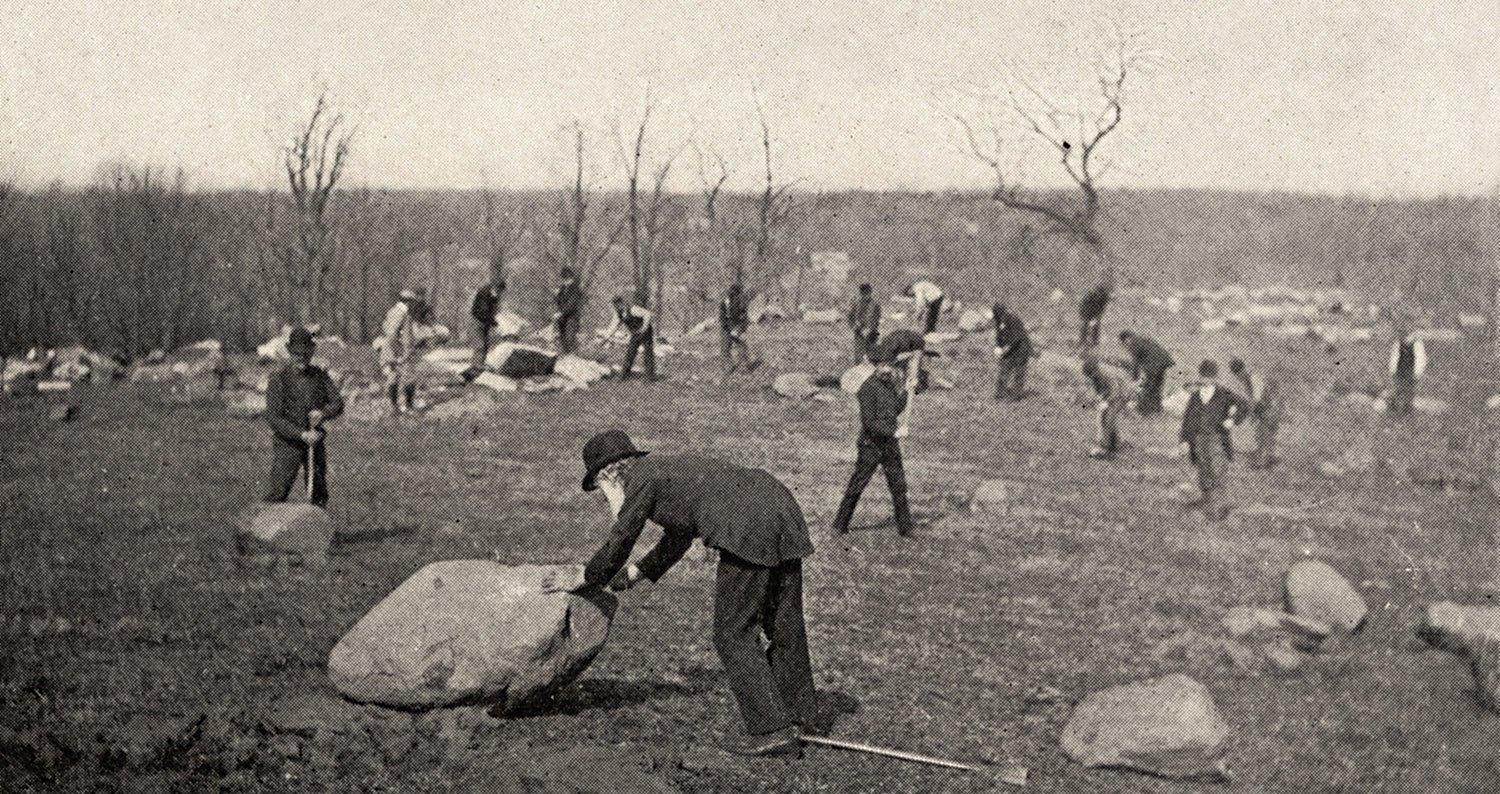

In 1894 the game got serious when representatives from the major clubs in the northeast converged on New York City and formed what would eventually become the USGA. Also in 1894 America’s first golf magazine, The Golfer, was published. The following year saw the inaugural U.S. Women’s Amateur and the birth of the course that became something rather more than its founders had wanted. Looking to get golf within New York City limits, a group of local businessmen who called themselves The Mosholu Golf Club attempted to get the city to co-fund construction of a private club at Van Cortlandt Park, which had been named for the city’s first native-born mayor. The plan backfired somewhat in that the city did help to build the course, but refused to close it to the public. Thus, the first public course in the United States opened July 6, 1895. The charming 9-hole (five years later it was an 18) had cost $624.80 to build—but there was no charge to play. This, along with having no set rules, quickly led to mobs of people and unruly behavior. Local papers bemoaned “the poor playing conditions, the unmanageable crowds, and a general lack of golf etiquette” (and they haven’t stopped since). Whatever the criticisms, Van Cortlandt—and, as they opened, New York’s other municipal courses—helped to popularize golf among the general population, women included, quickly building the game in the city and in the region as a whole.

On the administrative side, on the heels of the USGA’s founding, in January of 1916 a group of pro golfers and leading amateurs met at the Hotel Martinique on Broadway and West 32nd Street for a lunch organized by department store magnate Rodman Wanamaker. With a mind to improving golf equipment sales, Wanamaker proposed the foundation of the professional organization that eventually became The PGA of America. By October the group was hosting its first PGA Championship, and the following year it was entrusted with selection of the site for the 1917 U.S. Open.

On the private side, club development was well underway and here, too, NYC was having an influence. The prestigious New York Athletic Club had formed its Nyackers golf group in 1913, and in 1921 it celebrated the opening of Winged Foot Golf Club in Mamoroneck, NY. While there was no formal affiliation, the club took its name from the NYAC logo (a winged foot). Within a few years the country had its first golf museum (founded by the USGA in 1936), though it didn’t have a dedicated space. Its first donation—Bobby Jones’ “Calamity Jane” putter—was exhibited with other memorabilia in various bits of free space around the USGA offices. In 1950 the group purchased a brownstone at 40 E 38th Street that became the first Golf House and dedicated two floors to the museum, formally creating what the New Yorker called “the Louvre of the golfing world.” (Today, Golf House and the museum are located in Far Hills, New Jersey.) While the administrative and business sides of the game were being organized, city golf’s social identity was going through an evolution of its own—and it wasn’t always pretty.

A Tough Crowd

“The woman golfer is not popular on the links. Occasionally a fairly good player commands admiration, but for the most part they are barely tolerated.” The pre-feminist 1910 Times piece about golfers in Van Cortlandt spared no one. In addition to lamenting women on course, it derided fathers who brought their kids to play (“This ain’t no daynursery”), ridiculed the overweight (“One woman who could not have weighed less than 210 pounds toiled up the steepest hill on the links one particularly hot day… Another woman, plainly many pounds less in avoirdupois but still chunky enough to need reducing, passed her going in the other direction”) and even took a swipe at the game itself: “Not all fat people go in for the game. There is the dyspeptic, the man who cannot sleep, the man with the sluggish liver, the moribund individual who needs a new outlook on life, the old man who wants to get young again.” Mean-spirited it was, but it’s also confirmation that the New York game has always been tough. There’s no denying it: golfers here are just different.

“I think so,” said Dr. Ira Warheit, a Brooklyn resident who grew up on Staten Island. “You’re dealing with a different mentality, not a country club mentality. You’re dealing with guys who could easily get angered and get into disagreements if someone’s playing slow.”

A 1955 Sports Illustrated article by Jane Perry confirms that it has always been thus. Writing about Dyker Beach Golf Course in Brooklyn, in a piece entitled “Brooklyn’s Mad Golf Course,” Perry gave a colorful description of Dyker—and, by extension, of New York golf as a whole: “Once a foursome starts on its way, it is at the mercy of eight people, the foursome immediately in front and the foursome behind. The four in front will hold up the game by searching for balls, by mysteriously acquiring friends and becoming a sixsome; they will accuse the four behind of cutting in and trying to play past them. Sometimes they will charge at offenders with raised clubs—especially the females, who are, in this respect, the more deadly of the species Golfer Dykeriens.

“The four behind will snap and snarl at the heels of the foursome ahead. If a player so much as stops to tie a shoelace, they will drive a warning ball whistling past his head. They are masters of the impatient stance, the sneering look, the ‘Hurry up, willya!’ cries of outrage.”

Far from farcical, Perry’s portrait of the course was confirmed when John R. Van Kleek, the course’s architect, penned a letter to SI praising her work: “I recollect with deep emotion dodging golf balls during the last days of construction, listening to the gripes of at least a thousand golfers, testifying in the courts and listening to the low-down on myself, the golf course and the park department in the bars along 86th Street,” he wrote. “The training I got at Dyker was so good that I went through three revolutions in Venezuela without batting an eyelash.”

Kleek, who also designed La Tourette in Staten Island and Split Rock/Pelham Bay in the Bronx, worked in Venezuela after finishing Dyker in 1935. That course has been seeing more than 100,000 rounds per year since the mid 1960s, illustrating another reality of NYC golf: crowds.

“What a dump,” reads a March 2018 Yelp review of Clearview Park GC in Queens. “Noisy, fairways were chewed up, tee boxes were pathetic… What a stinker.”

“If 5+ hour rounds are your thing, this is your course,” read another. One reviewer saw a bright side, however: “Highlights of my day at Clearview: 7+ hours at this dump; witness four groups of golfers on a par 3 tee box; took a 5-minute nap after each shot.”

Ball Theft

Besides crowds another facet of NYC golf is ball theft, so longstanding it might as well have its own rules of etiquette. In 1910 the Times blamed it on “Italian boys [who] lie in wait at convenient places and picking up balls skurry [sic.] away before the player appears in sight. Those who are not familiar with their methods spend much useless time looking for balls they will never see again, unless they happen to buy them from an innocent-faced caddie at some later period.”

Perry’s SI piece confirmed the practice was still happening 45 years later: “Golf ball snatching, a problem at all busy courses, has achieved the status of a science at Dyker. Among the most skilled snatchers are the small boys who operated on several fairways adjacent to the city streets. When directly accused, the boy might be standing on the ball or has just slipped it to an accomplice, but he is all snub-nosed, freckled and dirtyfaced innocence. ‘I ain’t got ya ball, mister. Wanna soich me?’”And finally, another New York Times piece, this one from 1995, warned that “neighborhood children sometimes dart onto the 16th fairway to steal balls”—a reality that’s still reported today in online reviews. The 1995 article went on to point out that ball theft was hardly the biggest hazard: “Two years ago, a morning threesome arrived at the 14th green to find a dead man dangling from a maple tree. A year or two earlier, a golfer had his cart stolen; he retrieved it a half-mile away and finished the round. Corpses are occasionally found on the opposite side of the lake in front of the clubhouse.”

All of that, plus online anecdotes telling of fights, more stolen balls and behavior that wouldn’t be tolerated almost anywhere else—“[My boyfriend’s] friend was chased by security… I remember hearing about him through their walkie talkies about some crazy guy who isn’t stopping in his cart. haha” (from a Yelp review in 2013, which gave Van Cortlandt three stars out of five)—all suggest that golfing in the city requires an open mind.

Access

But for all of the madness, the flip side of the eccentric nature of golf here is that the city achieves what so much of the golf world claims to want: diversity. It’s not uncommon to see the world on a NYC course: construction workers, plumbers, firefighters and cops golfing right alongside executives, chefs and accountants. The Flushing Meadows Pitch & Putt par-3 course is lighted, stays open until 1am and hosts local immigrant families from Haiti, Ireland, South Korea, Mexico and numerous other locations. Likewise, this writer has golfed Brooklyn’s Marine Park Golf Course plenty of times and has witnessed people playing in jeans and work boots, in suit pants and loafers, in beach attire and, sometimes, in golf wear. Nearly all NYC courses are available via the subway or bus service (see sidebar: Subway Etiquette) and NY resident prices mostly are reasonable: $42 weekdays/$52 weekends for 18 holes before 12pm, $32/$40 after 12pm, with heavily discounted twilight rates. The only exceptions are Mosholu Golf Course and the city’s newest public track, Trump Golf Links at Ferry Point Park, which have different rates. The latter was fraught with New York-Style drama even before its developer found the White House, with many city residents—who must pay $185 for a weekend round—feeling the taxpayers got a bad deal. Since the election the criticism has turned political, with some voicing displeasure in a more traditional New York City fashion: via graffiti. Vandals spray-painted the words “The New Colossus” on the course in September after Trump announced he’d be killing the “Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) immigration program, likely in reference to the poem of that name affixed to the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty, which reads in part, “give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses.”

Chelsea Piers, the site of so many foreign arrivals to New York City over the years, has suffered no such indignities. America’s premiere arrivals platform for some of the greatest ocean liners in history, the 30-acre site to which Titanic survivors were brought is today a tremendous sports complex and the site of one of the city’s greatest golf assets: a multi-tier driving range and instruction facility that’s become something of an icon over the years. With heated driving bays, city residents can stay sharp all year long, and there isn’t a hardcore golfer in NYC who hasn’t hit balls here, including some of the city’s better-known residents.

Movers & Shakers

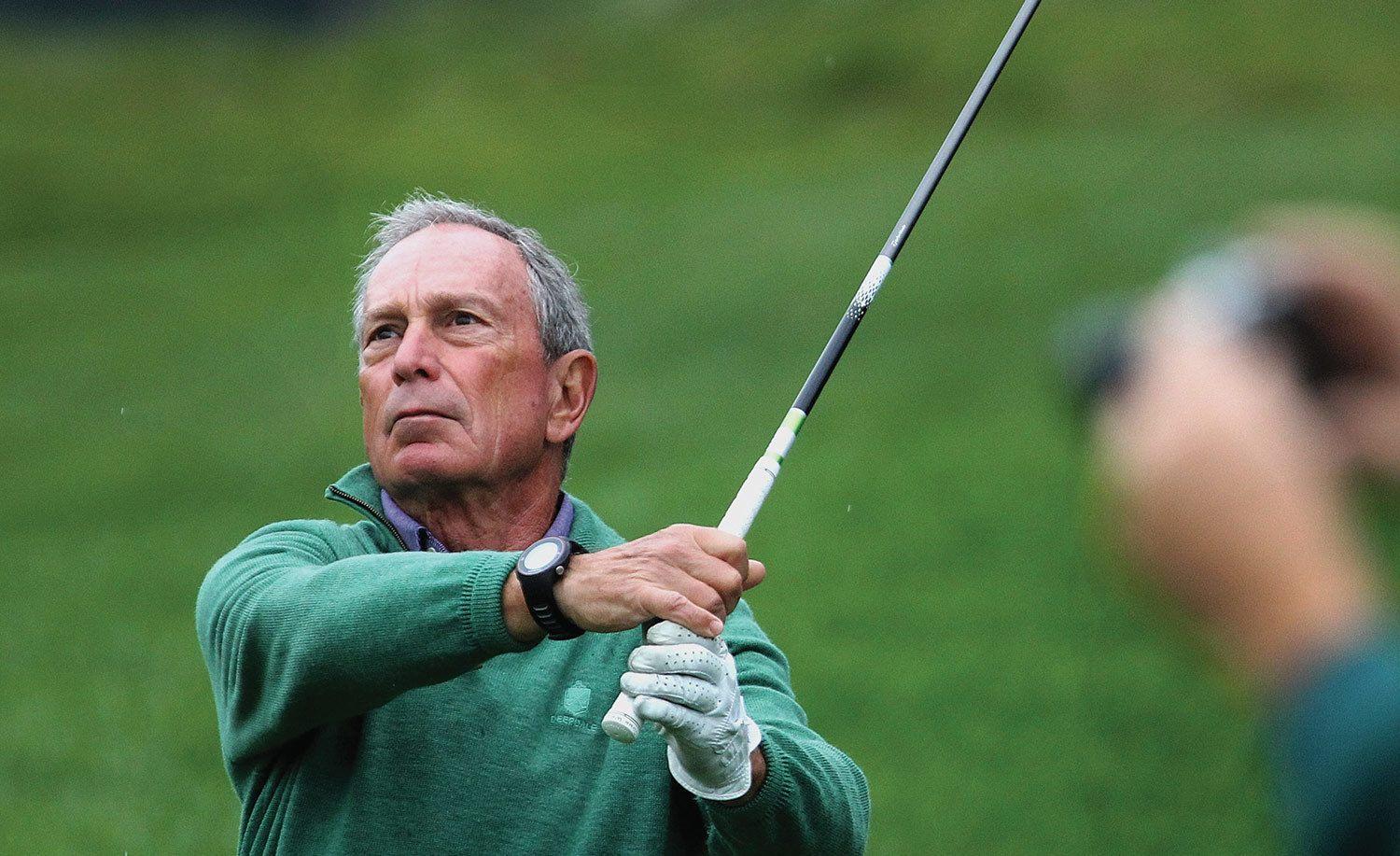

In 2009, The New York Times examined then Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s relationship with the game of golf, calling it “a foe with no term limits” for the enthusiastic but talent-challenged mayor. From the article: “He took up the game around 2000, but ‘you probably wouldn’t want to call that golf, what he played,’ said Daniel M. Donovan Jr., the Staten Island district attorney, who has played with Mr. Bloomberg for years.

“‘He was confused by it,’ said Morris Offit, a longtime friend and golf buddy of Mr. Bloomberg’s. ‘He felt that if he tried hard, gave it the appropriate attention and got good instruction, that he would improve rapidly.’ He did not.”

Bloomberg reportedly kept clubs in the back of his official SUV so he could sneak out and play a round or at least a few holes after appearing at a parade or speech. He was often seen hitting balls at the Randalls Island driving range in Manhattan, and he liked to go to nearby Westchester for a round now and then.

The President’s affection for the game is well known, and in the past he’s credited it with facilitating much of the business he’s done in NYC, including even the purchase of Trump Tower.

“Yes, maybe even Trump Tower,” he told me in 2013, in an interview for Kingdom magazine. “The people that owned the land, I got to know them through golf. And through that, through golf, I got to buy maybe the best piece of land in the United States, and that’s 57th and 5th, right there by Tiffany’s.”

Finally

New York City’s municipal courses collectively see more than 600,000 rounds per year. In 1895, the Times wailed about bad language, highlighting one player in particular: “It is a rare privilege to hear his expletives, and he seems never to be at a loss for new ones.” In 1955, SI observed that a Brooklyn course was “where the undershirt is a classic costume for hot summer days… and where the insult is the common and formal method of communication.” Nothing’s changed. Not really. You’ll still find characters on course: mayors and waiters, brokers and mechanics, mobs and hustlers and even potential pros. And that, really, is the essence of the sport here. Unlike anywhere else, golf in New York City isn’t just a game—it’s everybody’s game. Feel free to bring your clubs, just remember: If you feel like stopping to admire the views of the city while you’re on course, don’t.

Subway Golf Club Etiquette

Moving advice from the city’s top news source…

- When approaching the entrance, swipe your MetroCard first and then pick up your bag with both hands and guide it straight through, above the turnstile.

- If the train is crowded, try to stand at the far ends of the cars. You’ll be out of the way and also right under the air-conditioning vent on the newer trains.

- Use your rain cover while in transit. This keeps you from whacking someone in the arm with your sand wedge and also reduces the chance of dinging up that $500 driver when you bang it against a staircase railing.

- Despite the fact that subways are much safer than they used to be, don’t talk too loudly about that $500 driver.

- Don’t employ the double strap on your bag unless there’s no one else around you, which is not the case in most subway situations. Don’t be that girl.

Edited, from The New York Times On Par blog